How does one select a money market fund manager? Is it who offers the best rates, a manager linked to a relationship bank, a manager NOT linked to a relationship bank or the one with the easiest onboarding process? Hidden behind the reputation and the yields, there is a vast amount of work going on in the background by the manager and understanding what these are will help an investor make a more informed decision

When selecting a MMF manager we would encourage investors to use the universe of AAA-rated funds as a starting point in their analysis, as relying on the existence of a AAA rating as a ‘gold standard’ can result in a fund selection process that is skewed towards relative yield or based on yield alone. It is far from the case that all AAA MMF funds are fungible and carry the same risk with the market containing a variety of approaches to portfolio management, resulting in funds that differ significantly in risk profile. Understanding this heterogeneity is the key to manager selection; this requires investors to ask the right questions or, to put it another way, to ‘look under the hood’.

However, a list of questions is of little use without an understanding of why a particular topic is important and how the answer can illustrate differences between funds. In this article we will concentrate on that ‘why?’ For details on the ‘how?’ we’ve provided a sample questionnaire.

There are more than 50 questions in our suggested Request for Proposal (RfP), in a structured format designed to tease out how the responding manager approaches MMF management and help the investor gather the essential data and product features so that a better-informed manager selection can be made. These may be too many in practice but the list provides a useful universe to select which ones are most important to you. Even if you are happy with your existing selection of fund managers, the questionnaire may help you re-visit and review you existing portfolio to check they are still suitable. Below, we identify four key areas of differentiation between managers, explain why the topic is important and highlight the key questions.

Liquidity management

Why is it important?

Liquidity provision is one of two cornerstone objectives of any money fund. There are two distinct aspects to liquidity management that need to be examined. A manager should have robust and detailed processes to manage both assets held in the fund, and the fund’s liabilities to its shareholders.

Asset side liquidity management features a robust process governing the proportion of maturing assets due in one day, one week, one month, etc. This should be supplemented by a thoughtful approach to the proportion of transferable assets held and the likelihood of being able to sell securities in stressed market conditions. How these two considerations interact and are managed is at the heart of the asset side of liquidity management.

Liability side liquidity management is an equally important dimension to examine but is perhaps not so well understood. This consists of individual investor and collective client types (sector, geography, typical investment horizon) that form the fund shareholders. Diversification of the client base and how the manager monitors and achieves this is a strong area of differentiation between providers. Managers will adopt different strategies to client concentration, and this is an area of real variation given that, while MMF regulations require a policy in this area, it is left to the individual manager to design and implement their own approach.

Some examples of why client concentrations should be mitigated are:

- An MMF whose client base was heavily skewed to hedge funds, as its parent was one of the world’s largest prime brokers, lost 80% of its assets in two weeks during the Global Financial Crisis as the hedge fund sector had to meet heavy cash calls in a short period of time.

- During the UK’s ‘mini budget crisis’ in 2022, a GBP MMF whose client base had a concentration in UK pension fund clients with LDI strategies lost 23% of its assets in one day.

Therefore, it is crucial that a manager has policies in place that protect the fund and its shareholders from extreme AUM movements by actively managing client concentrations by client but also client type. At times it will be necessary to turn away new business or limit capacity given to a single client to ensure adherence to this policy. Therefore, it is important that this is controlled and monitored by the portfolio management team, and not a business development team, to avoid any conflict of interest.

Key questions – see D. Product – Investment Process

- Describe the portfolio construction process.

- Describe the process for managing asset maturities.

- How do you factor in the management of individual client and client sector concentrations into your investment process? If a client concentration policy exists, who owns the policy and controls client concentration levels?

Credit process

Why is it important?

Our first section examined the first primary objective of a money fund. This is the second: capital preservation. A money fund is a collection of individual investments, and as such, a credit risk management philosophy and process is another defining element of a MMF investment manager. The output of this process is typically referred to as an ‘approved list’ and this governs which credits are eligible to be included in a fund. The credit process can be approached in a variety of ways – and investors should make sure they understand and are comfortable with their manager’s strategy.

At one end of the spectrum of approaches would be an approved list that consists of the universe of A1/P1/F1 issuers with maximum permitted individual maturities and percentage exposure as permitted by regulation (397 days and 5% respectively). Such a framework is arguably too blunt to mitigate the type of risks inherent in an MMF. Default risk is one such risk, but a MMF needs to manage additional factors such as liquidity, price and spread volatility long before a default occurs. As an example, long-term issuer rating migration can have an effect on the price and liquidity of a security even while an issuer’s short-term rating is stable. A more considered approach might feature independent credit analysis (typically including a more granular internal rating scale) of the A1/P1/F1 starting universe to produce a ‘credit matrix’ where the wide range of credit quality of the A1/P1/F1 investment universe is constrained by assigning limits to each approved issuer by absolute maturity (six-month limit, say), and, concentration by maturity (a certain percentage in one month or shorter maturities, a lower percentage between one month and six months).

An obvious recent example of the need for proactive, independent credit research is Credit Suisse, who failed in March 2023 but whose troubles can be traced back several years. The slow-motion nature of Credit Suisse’s demise provides a yard stick to examine a fund provider’s credit process. More sophisticated managers will be able to provide a timeline of internal credit analysis, ratings changes and risk management actions that illustrate a dynamic, multi-faceted credit process.

Key questions – see F. Product – Research

- What are the outputs of the credit research function?

- How is internal and external research information incorporated in the decision-making and portfolio construction process?

- What distinguishes your research effort for this product from the competition?

A1/P1/F1 – context for a credit focus

The money market investment universe is often, erroneously, seen as a homogeneous landscape. Just as an AAA MMF rating does little to differentiate between managers, investments rated in the highest short-term category by a rating agency feature meaningfully different risk profiles. It is important to recognise that a short-term rating is a coarse measure of credit quality and that should generally be used to define an investment universe from which more fine-grained analysis can be undertaken.

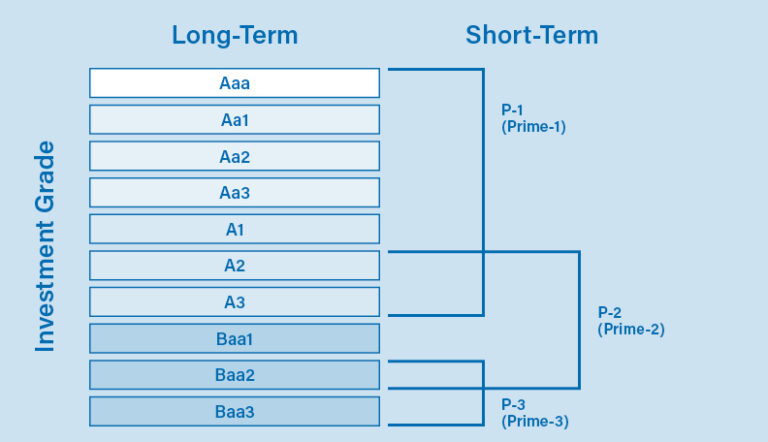

To illustrate this, consider the differences between long-term and short-term issuer credit ratings; each rating agency has a slightly different but analogous approach. For clarity we will use Moody’s Investors Service (‘Moody’s’).

Moody’s assigns short-term ratings to just under 4,000 distinct issuers. Of those, around 1,700 are rated in the highest category of P-1 and therefore nominally eligible for inclusion in an AAA money fund. Moody’s also assigned long-term ratings to issuers. The table below provides a means to map long-term rating to short-term ratings. It is immediately apparent that a P-1 short-term rating can be assigned to issuers with vastly different long-term ratings. An issuer with both long- and short-term ratings can be rated P-1 short term while being assigned any one of seven long-term ratings (from A3 through Aaa).

People

Why is it important?

Liquidity and credit management are the heart of an investment manager’s process. A process is implemented by people, and a prospective investor must investigate the experience and competence of those people. This extends beyond the portfolio managers: credit researchers, investment specialists, portfolio analysts, risk managers, client management and service, and governance are all vital parts of the team that ultimately delivers the investment solution. Relevant experience levels and team stability are paramount. A market event or crisis is a unique mix of idiosyncratic factors, from the catalyst of the event to numerous other variables including market dynamics around liquidity and credit, prevailing regulatory environment, macroeconomic factors, and fiscal and monetary policy. A manager’s ability to draw on experience from past crises will allow them to look at the individual factors objectively.

Money market fund portfolio management is a highly specialised discipline – it should be an asset class in its own right – and the more sophisticated managers are organised and resourced accordingly. Prospective investors should examine years of asset class experience and ask about specialisation, for example managing a GBP portfolio is different from an HKD portfolio. As there is often overlap in the credits used across different currency MMFs, having investment professionals in multiple locations managing those different currencies can provide early warning signals to a change in an issuer’s behaviour in one market not yet seen in another market. Location of investment professionals is also important to building experience and ability to manage the subtleties of local markets while maintaining a globally consistent risk management framework.

Key questions – see J. Product – Personnel

- Please can you provide your latest organisation chart for your portfolio management and credit research teams?

- What are the years of relevant investment and asset class experience of each team member?

- List the office locations from which the investment teams operate.

ESG approach

Why is it important?

The impetus for more sustainable cash investment solutions, such as ESG MMFs, continues to grow. Investors seeking such strategies should demand that the solutions offered are robust, credible and are meaningfully differentiated from a non-ESG fund. Just as reliance on an AAA MMF rating masks a spectrum of risk and return profiles, an over-reliance on the EU’s Sustainable Finance Directive Regulation (SFDR) classification could lead an investor to conclude that all ESG solutions are the same. In reality, each manager’s ESG investment methodology will be different, and the impact of these methodologies on a MMF’s investible universe can vary widely. It is therefore important to consider if the methodology results in a quantifiable impact on the investment universe; for example, by constraining a proportion of the investible universe by removing issuers with lower ESG scores. This focuses investment in issuers that are deemed better at managing E, S and G risks in their business. It is hard to argue the efficacy of an approach that fails to constrain the investment universe materially.

Alongside a constrained universe, a well-articulated and targeted engagement strategy can augment an ESG MMF’s value proposition to the shareholder. Any engagement should follow a clear theme or themes and have a clear purpose. Furthermore, understanding how ESG considerations are integrated into the credit research and portfolio management processes should be transparent and clear. Finally, the quality and experience of a manager’s sustainability team and resources devoted to liquidity products are analogous to the previous section on people and will help the investor in their assessment of fund and manager ESG credentials.

Key questions – see E. Product and ESG Integration

- How is ESG integrated into the fund?

- Are ESG research views captured in research reports? ? How do these ESG views/analysis in research reports feed into the overall issuer ranking/view?

- Please provide separate examples of E, S and G engagements, noting where they have been successful, are in progress or have yet to lead to change.