Recent turmoil in the banking sector, with the collapse of several banks in the US and Europe, has shone a spotlight on two key areas of risk for treasurers – liquidity and credit risk. Why?

1. Increased liquidity risk in US treasuries

- Evolving regulations forcing banks to hold capital against treasuries, as part of the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR). This resulted in primary dealers less willing to hold RWA-expensive treasuries with their proportion of traded treasuries falling from 14% to 2%. Although hedge funds, high frequency traders, and other institutional investors have increased their holdings, the pool of stable investors has shrunk significantly, and they are not able to fulfil that role.

- The US government’s deficit has grown and has continued to outpace the already constrained primary dealers’ ability to absorb extra treasuries. The withdrawal of quantitative easing in 2022 has exacerbated this issue. Together, this greater supply and the more limited ability to accommodate it has led to a systemically more fragmented and fragile market.

- suspending the SLR rule for treasuries (2020-21), since when holding them has become expensive again

- initiating a large bond purchase scheme (2020-22)

- changing the Federal Reserve’s discount window to price treasuries held as collateral at par, rather than according to market price (2023)

- use of the standing repo facility, instituted in 2021 (2023).

- to obtain better insights of the treasury market with improved data

- a central clearing house for treasuries, replacing the primary dealers.

Liquidity risk: actions for treasurers

- overnight liquidity

- client concentration.

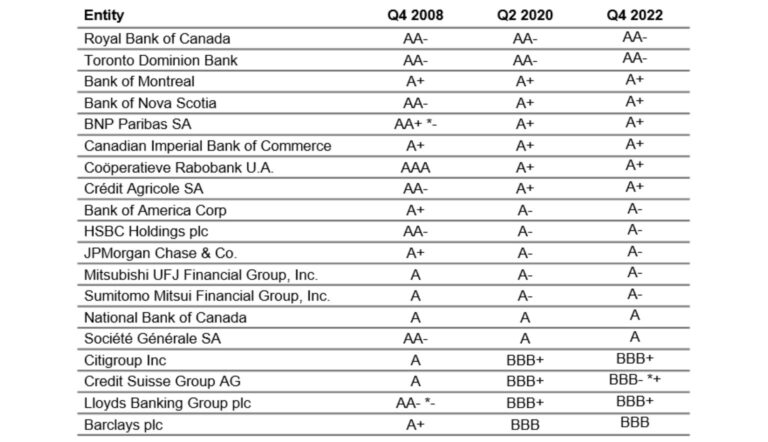

Table: S&P Long-Term Credit Rating

Source: Bloomberg, HSBC Asset Management

2. Credit risk

Credit quality of corporate issuers is of particular importance in a higher interest rate environment and economic backdrop that is uncertain, with sticky inflation and low growth. However, as of the end of March 2023, the majority of global systemically important banks have had their credit ratings affirmed (see table above), and the global banking industry remains a high single A-rated sector .

Although the larger banks are relatively well positioned today, areas of credit risk remain. These include:

- a risk of commercial real estate defaults

- a potential rise in general levels of non-performing loans

- rising interest rates affecting the ability of sovereign issuers to service their growing debt burden leading to country downgrades or credit watch, which may in turn affect the ratings of banks domiciled in their jurisdiction.

Credit risk: actions for treasurers

Treasurers need to understand what fund managers are investing in, especially following recent bank collapses.

In addition, treasurers should:

- understand how the fund manager manages credit migration. Do they proactively approach credit by managing maturities for specific issuers? Do they have internal teams monitoring credit risk or do they rely on the major credit rating agencies

- monitor if the fund managers have an appropriate focus on those banks (and countries) where downgrades will either decrease liquidity or result in a rating that is lower than permitted for a rated MMF

- monitor credit migration from a sovereign to a resident bank and also across banks in the same geography/sector.

Pay attention

While a broad-based downgrading of the banking sector is not expected, the possibility remains for a more selective re-rating of individual banks and country banking sectors. Credit assessment processes should flag issues in advance and, even if the outcomes are worse than expectations, an investment focus, as detailed above, will allow treasurers to effectively manage them through any period of ratings changes.

Above all, treasurers must continue to pay attention to liquidity and credit risk – especially below the surface. One storm is over but there may be others on the horizon.